PUNK DAMAGE 2.0

An old affliction adapts to AI complicity

“Punk damage” is the unfortunate name for a very real condition that only afflicts one demographic: Generation X (to which I belong). I’ve read the term attributed to both the artist Edgar Fabián Frías and the book The Lesbian Lexicon, which defines it as “the sordid underbelly of self-limitation that comes directly from having come of age in a punk scene; often marked by an extreme distaste for the making or spending of even small amounts of money.”1 Personally, I’ve experienced this phenomenon as something much wider than an aversion to making money. Most sufferers of “punk damage” endure it as an internal voice.2 For me, it was a Greek chorus in a theater of the absurd.

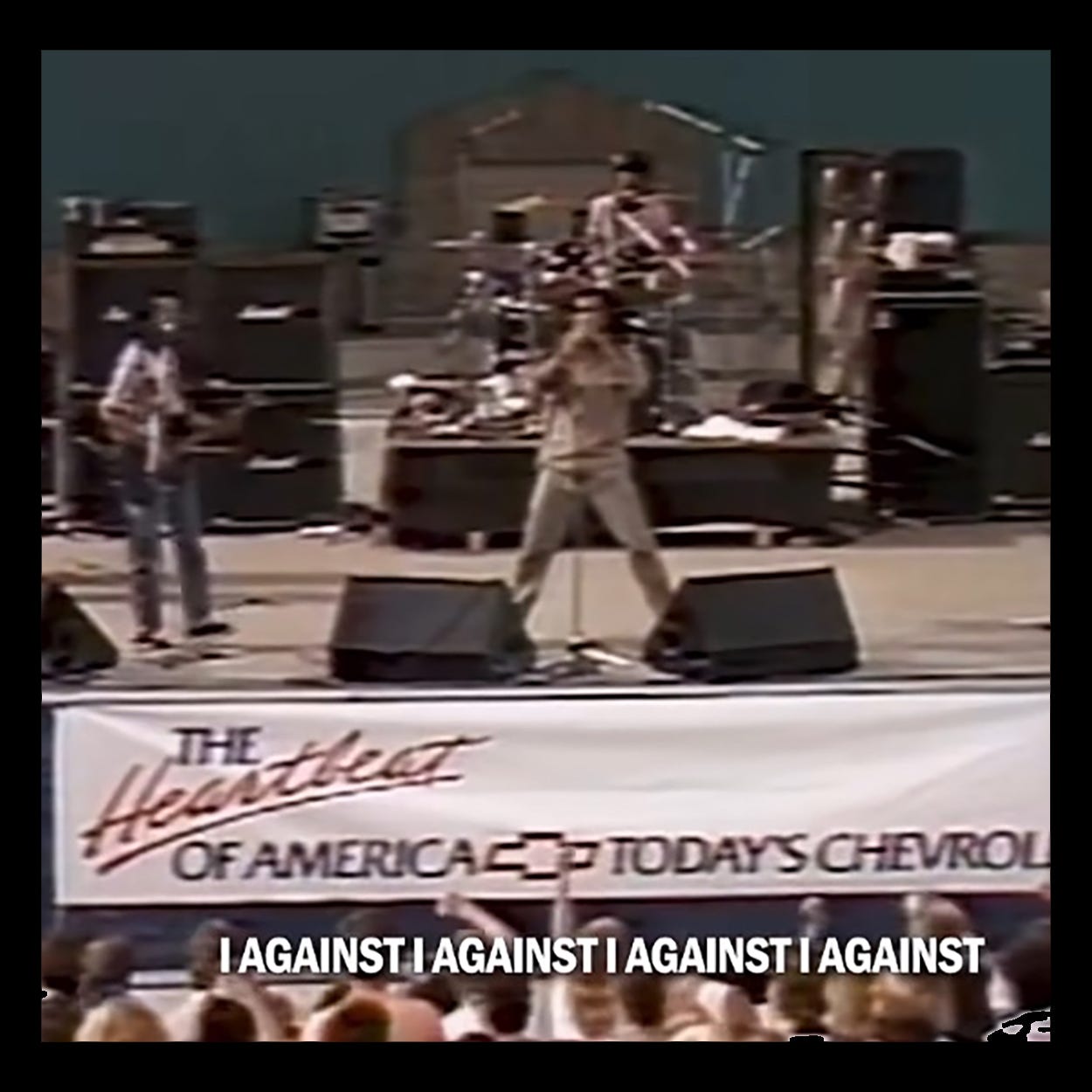

Being a band member, fanzine guy, and indie record-label owner gave me prolonged exposure to this chorus. Mailorder customers ranted to me about the evils of the copyright symbol. One time, on tour, a stranger admonished my band for fueling at Shell, as if there were more ethical gas stations. Another time a stranger wrote to me, outraged that he’d found an 8” EP I’d released selling at Tower Records for $5.88. He was so angry he underlined the amount three times.3 Then there was the time I was pilloried in print for having the audacity to sell a postpaid fanzine for one dollar. “Don’t believe the hype,” wrote the apparently serious reviewer. “One of the biggest zine rip-offs I’ve ever seen.”4

But in a dozen years of running a record label, no one ever scolded me for making non-recyclable, non-biodegradable consumer products. No one ever questioned the shrink wrap that swaddled many of my label’s albums, or the wisdom of releasing noise CDs clearly destined to become landfill. Copies of every release will exist long after any living memory of the documented bands has vanished from the Earth. On a long enough timeline, every record becomes refuse. Vinyl and shrink wrap last 500 years (although after a few centuries they shed their unsightly pupae forms—garbage—and become microplastics, free to flitter on the breeze or settle in bloodstreams). CDs are only playable for a century or so; their polycarbonate base layer can linger for a millennium.

It’s an odd thing to get correctly called out for the wrong offenses. I was never clear on which moral lesson I was supposed to have learned from the experience. Over time, I developed the slight vigilance of someone who has managed to get their schizophrenia under control with medication, but who remains always nervous that the voices will pipe up again.

Just this year, I’ve been hearing the chorus again. Spurred by new books like Empire of AI and If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies, public knowledge of AI’s ravenous appetites—for water, power, data— has exploded, often showing up in scolding comments under any video that uses AI. The gist of these comments is that any instance of AI is catastrophically bad for the environment. There is no perfect consensus on precisely how many resources generative AI uses, but there is a consensus that the vast amount of those resources is spent in training, not individual deployment. Making a short video using AI takes the same electricity and water as watching that video twice.

As a kid, I loudly renounced microwaves. I did the same thing in my twenties with cell phones. I’m not making the same mistake with artificial intelligence. I have need of small amounts of AI. I use it for transcription, and not just because it’s one-sixth the price of human transcription, but also because I find the idea of strangers listening to my unedited conversations repugnant. I rely on my phone and computer to read my own text back to me, a form of pre-LLM AI. I would gladly use it to read and summarize letters from people I do not want to hear from, even with the foreknowledge that I’d be placing personal information at risk of data harvesting.

Last month, I started using a face-swap app on my Instagram account. It seemed like an easy way to stay active online, which checked off one box for staying connected to humanity. In my comments—something I’m told that I, as a writer, should engage with even though a quarter century of Internet experience violently tells me otherwise—I detected pips of distaste that I’d used AI. I considered making a separate little video detailing the amount of water I’d personally forgo every day to make up the deficit, but the joke seemed to carry the risk of generating more ill will.5

I’d presumed all of this was covered under the tacit agreement of mass complicity each of us re-enters into every morning when we wake. I don’t shop on Amazon, but I’m fully aware that I must engage with the company every day of my life through Amazon Web Services, which runs a third of the Internet. Whenever I find myself on a flight, I feebly hope a lifetime of childlessness and hybrid driving and not eating red meat somehow zeroes out my carbon. And every night when I re-load Instagram onto my phone, my assumption is that we’ve all collectively agreed to just sort of do this incredibly shitty thing that is social media, and that the trade-off—communications with other people beyond the boundaries of our physical day-to-day lives—somehow equals all the harm being offloaded to parts of the world I don’t interact with.

And it is a grubby and shitty thing we do. Forget the carbon burden of cloud computing and social media (Instagram itself squirts out two cross-country flights of carbon per year per user). The manufacturing of phones is damning enough. Each device requires the user to traffic in rare earths like neodymium and dysprosium, each finite, each requiring cheap labor to extract. Other people, people that will never be met or even seen, must mine the copper, nickel, and lithium. Farmland and rice fields must be paved for new smartphone factories. Aquifers must be contaminated by arsenic, cadmium, and lead, sometimes sending floods of dangerous sludge through villages. Tantalum capacitors require vast, otherworldly pits into which hundreds, sometimes thousands, of anonymous humans must descend and harvest coltan. Every month, another mountain of obsolete phones—6.8 billion pounds—must be found a new home.

Yet we see these things bemoaned less than a morsel of AI usage. The language of “punk damage” provides a clean way to draw distinct lines in this web of abstractions, and that might make those distinctions comforting for some—but it does not make them correct. You are reading this on a screen right now, and therefore you’re in it with the rest of us. Welcome.

I’d define it more broadly as a fear of selling out, a concept lost between generations. Gen X’s definition of authenticity was passive, defined by not exchanging personal integrity for monetary gain. Subsequent generations seem to view authenticity as something active— “being true to one’s authentic self”—and thus fully compatible with brand sponsorships.

I’m using quotation marks because I don’t want to normalize this term. It needs a real name, one that infantilizes neither speaker nor subject. Other generations get cool-sounding problems like “conspicuous consumption,” “crushing debt,” or “brain rot.” “Punk damage” sounds like something you’d write on your pants in eighth grade.

He’s now an editor at Wired.

To state the obvious for anyone who’s familiar with my work from the 20th century, I deserved these comments, if only from a karmic standpoint.

That would be two cups of water, or 1/7 the recommended intake for an adult male. For comparison, one hamburger requires 9,600 cups of water to make.

Our "sellout" behaviors in the 90's seem almost quaint in comparison to the modern shit show.

i think "corruphobia"-- fear of corruption--is a truer phrase for the gen x punk trauma. but pretty meh as a catchphrase. gonna workshop it.