‘JEWFACE’ TRENDED ON TWITTER last week. At first glance, it looked like another small little win for the Nazis (a week earlier, ‘JEW YORK,’ burbled up to the What’s Happening sidebar). But this trending item came from the left, not the right, playing off ‘blackface’ in protest of the prosthetic nose worn by Bradley Cooper in his role as Leonard Bernstein in Netflix’s upcoming Maestro. People had beefs. Some posters called the nose ‘ethnic cosplay.’ Others were upset that a Jewish actor with a real nose didn’t get the role, or were angry at Elon Musk for allowing the term to trend, or took the opportunity to complain about people ‘swapping genders’ in real life. Bernstein’s family came in hot. “Any strident complaints around this issue strike us above all as disingenuous attempts to bring a successful person down a notch,”—meaning... Bradley Cooper??— “a practice we observed all too often perpetrated on our own father.”

This era’s disputes over identity and casting will, inevitably, spawn their own generational backlash. The tools to effect this backlash are quite nearly complete. By the time today’s first graders are in high school, they’ll be able to ‘cast’ anyone, in any film, on any device. The social barriers to race-blind casting will buckle once the technological barriers come down. And this reconfiguration will happen inside a larger reconfiguration, one in which the Old Hollywood, in Los Angeles, will have to directly compete with the New Hollywood, the one on everyone’s devices. In (pre-strike) 2023, de-aging and re-facing exist as significant line items on a film studio’s budget. By 2030, these options will exist as buttons on a control panel, buttons that anyone and everyone will be pushing all day, every day.

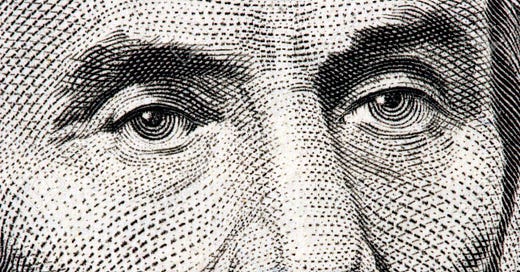

WHAT IF ACTORS PLAYED historical figures with the actual faces of those figures? Technically, we’re pretty much there. This trick wouldn’t be so effective with Maestro—I certainly had no idea what Leonard Bernstein looked like before this kerfuffle—but with nationally known faces it could mean something profoundly new. Imagine Spielberg’s Lincoln with the actual face of Abraham Lincoln saying the lines. Imagine those features, burned into all of our minds from lifelong exposure, whispering and laughing and flexing jaw muscles in deep deliberation. Imagine him reading casualty reports and whispering the word ‘fuck’ to himself. Film actors performing ‘in face’ would certainly solve one previously unsolvable question; how much should an actor portraying a real person actually resemble that real person? This would take care of performances where the actor looks nothing like their subject (Michael Shannon as Elvis, Tom Hanks as Mr. Rogers), and other, more problematic casting (a darkened Zoe Saldana as Nina Simone, a grotesque Joseph Fiennes as Michael Jackson). It would be bad news only to the very small pool of actors who can play historical figures with such force that they seem to channel a spirit, not impersonate a celebrity.1

This new definition of performance will open all sorts of weird possibilities.2 Not every actor has the range of Lincoln’s Daniel Day Lewis; if the real-life protagonists’ face is already fixed as its true form, there’s no technical barrier to the director bringing in one or more pinch-hitters to tighten up a line or two. There’s no reason multiple performers can’t inhabit the same body, reducing actors to gig workers doing punch-up work, even as directors gain the ability to reach down into a film and finely tune every performance like a piano string.3

The WGA and SAG-AFTRA strikes are the current frontline in the battle to keep Hollywood human. Perhaps historical figures will get perpetual protection over their own faces. Maybe actors will too. But there’s momentum in the other direction. Consider: there’s no longer any need for the kinds of full colosseum spectacles like the chariot race in Ben-Hur, with its 1500 extras. Lord of the Rings director Peter Jackson ended that when he commissioned Massive, software that allowed filmmakers to build their own crowds and armies. So there no longer have to be crowd scenes. We are just about at the point where filmmakers will no longer need extras. Soon, they won’t need any actors at all.

Anthony Hopkins’ stumpy, hunched take on Richard Nixon was so forceful, I remember having a hard time remembering the real Nixon’s face when I left the theater. I had the same reaction with Alec Baldwin’s Trump on SNL. Days later, I’d hear the real man’s voice on my car radio and picture Baldwin’s absurd pout.

Aging will change. By his 70s, Tom Cruise will have the option of performing as his younger self, physically for as long as he can hack it, then as a voice actor when he can’t. And films won’t be able to get away with improper younger versions of actors whose youthful faces we’re already familiar with (Kiernan Shipka in Wildflower / John Cusack in Hot Tub Time Machine / Joseph Gordon-Levitt as a 30-something Bruce Willis opposite the actual 57-year old Bruce Willis in Looper).

Or to have young actors provide the physicality that older actors cannot. One scene in Scorsese’s The Irishman shows why. A de-aged Robert DeNiro assaults a grocer. He plays the scene as his 30-something self, but the actor was 75 during filming. His motion is stiff and elderly. The scene reads like a middle aged man play-fighting an old man.

The spectrum of Michael Shannon as Elvis on one end, and AI 'in-face' on the other is a lot to chew on! Michael Shannon as Elvis is one of my favorite things, btw.