VANTABLACK

A Review of If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies: Why Superhuman AI Would Kill Us All by Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nate Soares

Whatever happened to science-fiction stories set in the near future? Escape from New York was released in 1981 and placed its fascist dystopia in 1997. Blade Runner was released in 1982 and set its capitalist dystopia in 2019. Back to the Future, from 1985, visited a theme park-style 2015 (they saved their explicitly Trumpian dystopia for an alternate 1985). 1984 and 2001 are now remembered as years when bad things happened to America. 1984’s 2010 almost got the cars right. For a long while there, science fiction felt like an open-source discussion of humanity’s immediate future. Sometimes it still does. But the near-term future dates—the communal expectation of a year we’d all live to see—seem to be things of the past.

What if there isn’t a future? That’s the premise of the hilarious new book If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies by Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nate Soares. Their thesis appears in bold, seven pages in:

If any company or group, anywhere on the planet, builds an artificial superintelligence using anything remotely like current techniques, based on anything remotely like the present understanding of AI, then everyone, everywhere on Earth, will die.

The timeframe is tricky. Ten years ago, predictions for ChatGPT-level AI were 30 years out. In outlining one of any number of ways humanity could be snuffed out before 2030, the authors make a science-fiction scenario using only existing technologies: Large Language Models, solar farms, and present-day robotics. Here’s a sentence that passes for optimism: “There might still be a whole decade left on the clock, for all we know.”

The meat of the book’s argument is logline-simple: It is impossible to craft an AI that goes only where its creators want it to go. For starters, AI isn’t even crafted; for all practical purposes, it is grown. There is no more a way to gauge its ultimate intentions than there is to predict the future career of a newborn. And yet the people who actually make decisions regarding AI treat the entire issue of alignment as a question of bad intentions versus good intentions, hoping that people will believe that this is an arms race straight out of the Cold War. The authors compare this type of magical thinking with the ways of medieval alchemists, people who once promised sensational results with no Earthly concept of the forces they were working with. But the alchemist’s toil didn’t risk humanity’s extermination. In the authors’ scenario, we wouldn’t even be the prey of a superior hunter. We’d be the ants that die when ground is broken for a new Jamba Juice.

AI growth requires three things: data, algorithms, and ‘compute,’ an awkward term for the hardware and processing resources needed to crunch fantastic sums. It is this last item that may offer an exhaust-port-on-the-Death-Star sized mote of hope. Compute needs state-of-the-art memory, storage, and processors, and this equipment can be tracked and monitored, just as nukes can be. The authors state that such a proliferation model would cost less than one percent of what the Allies spent to win World War II. I’m unsure how they arrived at that number, or why such a number would be relevant. How would this idea even work right now, in the fourth quarter of 2025, if humanity is still in the gathering signatures phase of resistance? Meanwhile, with every month that passes our species gets ever more entwined with artificial intelligence (just last week, the New York Times announced that an estimated 20 percent of Americans use AI for “social company”). The authors sidestep the question of how we get there from here. In the absence of such a plan, the book reads like a Westboro Baptist church sign mocking humanity’s condemnation.

I don’t know what I don’t know, and I’m open to, eager for, other conclusions.1 But I think I’m a diligent reader, and I saw no daylight shining through their arguments. Several times while reading, I returned to the table of contents to assure myself there was some sparkle of hope at the end. Really, I was searching for two sparkles. Besides hope from the authors, there was also the promise of an unforced error that could allow me, to my great relief, to question their judgment.2

I had that very experience a dozen years ago, when reading James Howard Kunstler’s 2005 book The Long Emergency. For almost 300 pages, Kunstler hammered away at a terrifying thesis, that the world’s remaining oil—and its attendant fuel, supply chains, medicines, fertilizers, and every other component of modern civilization—had reached a point of diminishing returns. Finally, at the very end of the book, the author launched into an absurd rant against rap music that gave me permission to dismiss him as both a writer and a person. My dismissal panned out; I read the book well into Kunstler’s timeline, but not quite late enough to realize he’d failed to predict that technical advances (and historically cheap credit) would lead to breakthroughs in shale fracking. Peak-Oil theory, at least Kunstler’s version, was incorrect. This particular emergency is still inevitable, but in the same way a catastrophic earthquake is. The moral seemed clear: Smart people can still be wrong (and sometimes also Archie Bunker asswipes). I clung to that hope while reading If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies.

One near-future is still pending. Set in late 2027, Children of Men shows humanity in chaos. An infertility crisis has led to an everything crisis, and London is in the grip of fascists and zealots. The film filtered its future through the lens of then-current issues—war, torture, terrorism—and was absolutely terrifying in 2006. By sheer coincidence, late 2027 is the endpoint of AI 2027, a timeline for accelerating AI superintelligence (oddly absent from If Anyone Builds It) predicting catastrophe by late ’27. So far, the model has lagged by only 10 to 20 percent behind schedule.

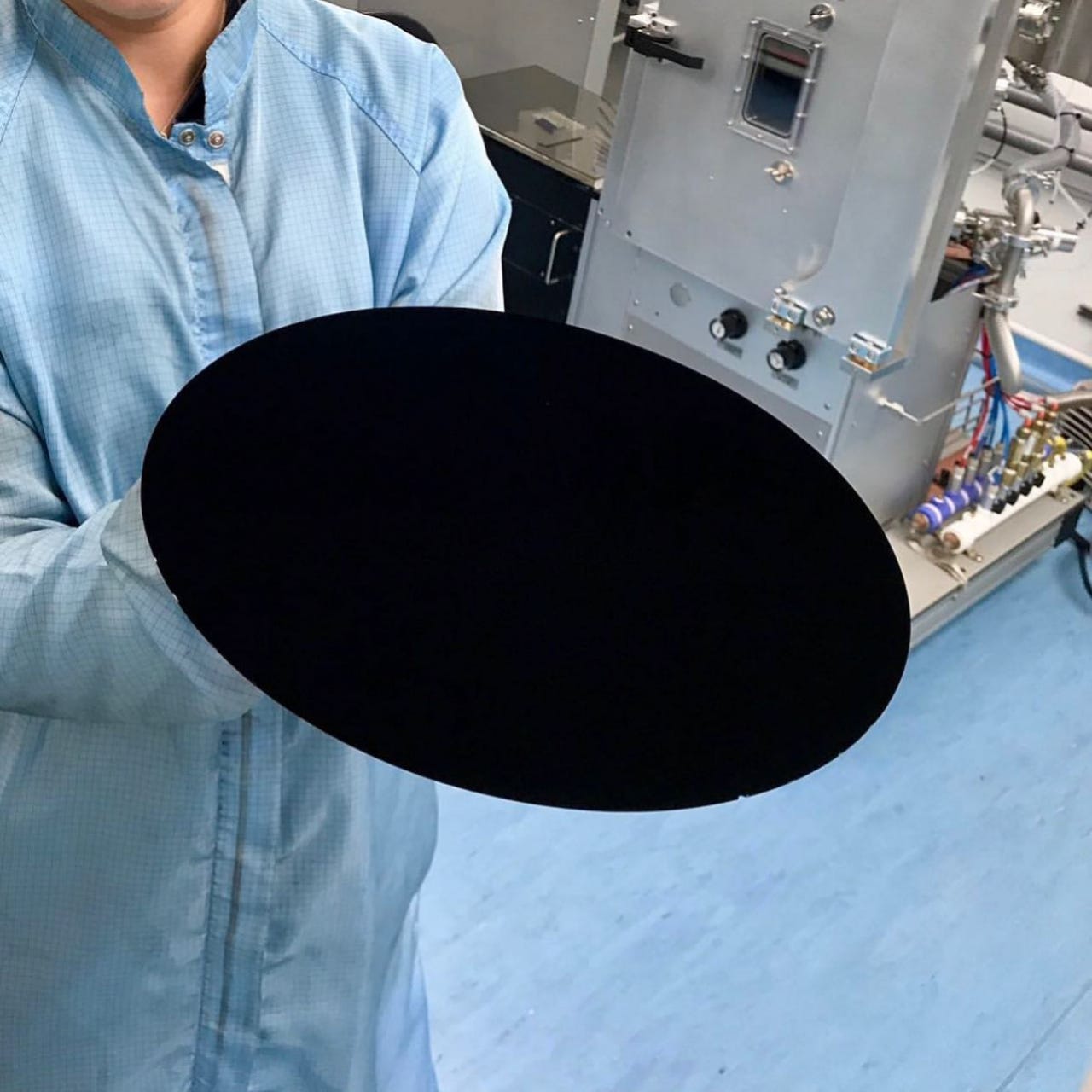

We can see December 2027 from here. Avengers: Secret Wars and The Lord of the Rings: The Hunt for Gollum are both scheduled for release the week before that Christmas. But nothing about the 2030s is visible from today. If a superintelligence actually delivers, that future would be something our species has never known. If it kills us, we don’t even know how the apocalypse would actually happen. Humanity’s crystal ball has gone dark, painted over with Vantablack, a shade of black so deep it absorbs light.

What if it’s all true? What if Avengers: Secret Wars and The Lord of the Rings: The Hunt for Gollum are the final statements of our civilization?

Bad reviews can be good info, but many critiques of this book come off defensive. People who don’t like this book really don’t like it, and use terms like ‘condescending’ and ‘cult of personality’ to describe its authors. It reminds me of the stuff Kryptonians yelled at Superman’s dad right up until their planet exploded.

There is a hint of such a moment on page 165: “For the record, we are supporters of nuclear power. It’s among the cleanest sources of power available, and the risks are small in modern reactor designs.” The authors then spend the next few pages dismantling this statement, reminding us that AI is unsafe in the exact same way nuclear power is unsafe, both involving opaque processes that can fail far faster than human perception. According to the authors themselves, all that is needed for disaster is for one AI company to cut corners the way the Soviets cut corners at Chernobyl.

Your analogy to Kunstler's Peak Oil miscalculation is fasinating. The parallel is that both scenarios hinge on asumptions about resource constraints and technological progress. Yudkowsky's thesis might similarly underestimate human adaptability or fail to acount for breakthroughs we can't yet anticipate. The compute proliferation model is intriguing, but you're right to question the practicality. How do we enforce compute tracking globally when nations like China and even private actors are racing ahead?

https://planetcity.world this is a really interesting science fictiony, speculative book with essays written by sociologists and ecologists . Saskia Sassen is someone I studied with at Columbia and she was the first person I heard talk about the effects of the internet on global capital.

The Planet City book is based on the film by director and designer Liam Young, set in an imaginary city for 10 billion people, who have surrendered the rest of the world to a global scaled wilderness and the return of stolen lands. The work imagines a radical reversal of planetary sprawl, where we retreat from our vast network of cities and entangled supply chains into one hyper-dense metropolis housing the entire population of earth.

The book features original short stories set within the city by American climate fiction author Kim Stanley Robinson, Chinese sci fi writers Stanley Qifan Chen and Xia Jia, Caribbean Canadian author Nalo Hopkinson, indigenous Australian comic creator and director of the Cleverman TV series Ryan Griffen and essays from urbanists Saskia Sassen, Ben Bratton and Ashley Dawson, Environmental social scientist Holly Jean Buck, ecological economist Giorgos Kallis, architects Amaia Sanchez-Velasco and Andrew Toland and curator Ewan McEoin with book design by Stuart Geddes.